… About whitmore Hanger?

You probably do, because we’ve written about it in several places. However, given its importance to Grayshott’s environment and history we thought it was time to give it an article all of its own. Firstly, for those of you who might not know, Whitmore Hanger is the woodland on the steep slope on the village’s northern edge, running behind Beech Lane, the playing field, Waggoners estate, Applegarth and Flat Wood, and extending down to the roads of Whitmore Vale and Whitmore Vale Lane. It’s a very beautiful area, a haven for wildlife and much loved by generations of locals as a place to walk, play, court, forage and fly-tip.

Although to a casual eye it’s just ‘woods’, it has four broad zones which have different characters and histories.

- There is an area within the medieval enclosures associated with the old farms on the plateau, which is predominantly beech coppice with occasional oaks. The prevalence of beech here is a little mystery. It’s a native species, but why is it almost entirely confined to this area? Was there some sort of selective encouragement?

- The northern perimeter of this medieval enclosed zone is largely embraced by oak-dominant wood, with birch and yew creeping in, and a few beeches.

- Then, down in the bottom, there is an alder-dominated zone in the waterlogged ground around and below the spring line.

- Last, and least obvious, the eastern edge of Flat Wood has survivors of old oak coppice among the plantation pines.

The oaks are quite exciting – they are of the sessile variety, which is an indicator of ancient woods. Everywhere is pretty wild and powerful – steep, boggy, overgrown and with mysterious humps and bumps – a wonderful place for Puck to hang out with the Green Man and party with dryads.

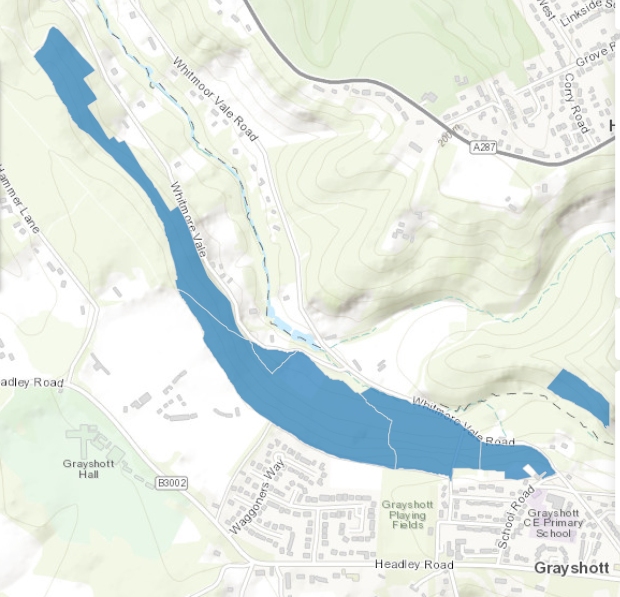

A location map of Whitmore Hanger. The red numbers 1 – 4 show the different zones described above.

How Old Is It?

Formally, the hanger is designated as a Site of Importance for Nature Conservation (SINC) and Ancient Semi-Natural Woodland (ASNW). But what do those things actually mean?

A SINC is a local authority designation for a place which has substantial nature conservation value on the basis of its habitat, wildlife interest or support for rare species. ASNW comprises two parts. The A – ancient – defines land that has been continuously wooded since 1600. The date was chosen because it’s the time from which documentary evidence becomes more available, and also because woodland existing by then had almost certainly occurred through natural generation rather then planting. The SN – semi-natural – denotes that it consists of native trees and shrubs, on undisturbed soil, but has been exploited or managed by humans. The relict oak coppice in Flat Wood hasn’t been designated, possibly because it’s not been officially examined, but it’s potentially yet another acronym – a PAWS – Plantation on Ancient Woodland Site.

Natural England’s map showing the area designated as ASNW (in blue). The potential PAWS zone in Flat Wood had not been identified when the map was made.

None of these designations confer any statutory protection, and despite Ancient woods covering only 2.5% of Britain’s land area and being recognised by the government as important natural and historic resources, they are still being destroyed at an alarming rate when they get in the way of money. These factors make the hanger a Very Important Place (VIP, now an official definition at Grayshott Heritage HQ), and one that needs to be taken care of. The loss of ASNW occurs not just through bulldozers and plantationing, but all too often it happens gradually through neglect, ignorance or misguided good intentions

This map made by John Greenwood in 1826 shows the hanger as the dark diagonal area across the centre. It’s strikingly similar to Natural England’s above.

To understand how old the hanger is, the justification for the ‘Ancient’ part needs some unpicking.

Many of us at school probably learned about the wildwood, the entirely natural forested landscape that developed across prehistoric Britain after the last ice age. It started as birch and Scots pine, followed by oak and hazel, then developed a more complex mix as a result of climate change and further species colonisation. It’s a concept largely overtaken nowadays, since historians realised that even mesolithic hunter-gatherers would have modified nature through their actions, for example by hunting to extinction the large herbivores that browsed the clearings and transported seeds in their fur and feet. It’s thought unlikely that any true wildwood survives in Britain.

Then there is primary woodland, meaning a site that has been continuously wooded since the last ice age – one which has biological continuity but has had human intervention. This is more easy to visualise in the hanger, which certainly hasn’t been beech wood since the ice age, but given its relief and geology may never have been enduringly cleared for agriculture.

The hanger’s Ancient designation was applied circa 1980 as the result of a biological study by (we think) the Nature Conservancy Council. We have a letter to that effect, although their workings and detailed report haven’t been published, as far as we can find. However, we know that they looked at the occurrence of marker species. These are types of flora and fauna which are known to be associated with Ancient woods. The association is usually due to specific environmental adaptations or very slow rates of colonisation. The NCC were the experts of their time, fully equipped with wellies, clipboards and magnifying glasses, so we can take their word for it.

To summarise – the hanger definitely isn’t wildwood, some of it might be primary woodland, and all of it is classified as Ancient. And, most of it has been thoroughly tweaked by human intervention.

Trees don’t have to be ancient to be charismatic.This lavishly nobbly beech might only be a hundred or so years old, but it’s delightful. If you take the last of our suggested walks at the end of the article, you’ll find it next to the footpath at Cane’s lower woodbank.

Just an aside here. The word hanger is Old English in origin, from hangra, meaning a wooded hillside. There are loads of them in eastern Hampshire. Where it occurs in old placenames it can be taken as an indicator of potentially ancient origin. For example, Oakhanger appeared in the Domesday Book as Acangre, meaning the ‘wooded slope where oak trees grow’, which is pretty conclusive. However, here the earliest occurrence of the placename Whitmore Hanger is in the late 19th century. We think it’s a retro-name applied by one of the local Victorian squires. The historic name is Grayshott Copse (and copse is derived from coppice, so accurately descriptive of the woodland type).

The Hanger as a Cultural Landscape

It’s a shame that NCC’s workings seem to be gathering dust somewhere. By now the specialists who did the work will be retired or returning to nature, but we’ve done some research of our own. We’ve concentrated on the hanger’s role as a cultural landscape, which amplifies the SN part of its designation. Cultural landscapes are the combined works of nature and humans, and they express a long and close relationship between people and their natural environment. Usually they’re the result of exploitation, which whether or not deliberate, results in a sustainable environment which can enhance natural values and preserve human traditions. The historic research sits alongside the pure biology to provide a fuller picture, and in our world of heightened environmental concern helps to inform conservation objectives and measures.

Our earliest documentary reference comes from 1184, where we learn that ‘Episcopus Wintoniesis debit dem. m. pro wasto bosci de Grauesseta’. Or ‘The Bishop of Winchester owes half a mark [6/8d or 33p] for the waste [and] wood of Grayshott’. This doesn’t mention the hanger but it tells us two things. First, it’s the earliest mention of our village’s name, which translated from its Old English roots means something like Grove Corner. The mention of wood is specific. In this context it’s taken to mean managed woodland, one exploited for timber and coppice, rather than just a random area of trees. So we can see that 840 years ago Grayshott was a woody place with an economic value. The bishop owed the tax or rent to the king, Henry II.

Next, still with the bishops, we find a later one describing the bounds of Woolmer Forest as recorded ‘en le tens Rey Johan’ – in the time of King John – so circa 1200. He records for the first time the name of Wytemore, and also the words ‘la porte de Graveschete’, or the ‘the gate of Grayshott’. Wytemore, our Whitmore, is derived from the Old English withig mere, meaning a willow pool. Very easy to imagine down in the bottom. Grayshott at this time was within the royal hunting reserve of Woolmer Forest, and subject to special laws. The gate, we think, was by the modern Fire Station and possibly used to regulate entry to the forest. A gate is useless without a fence or some other structure extending from it. Here then we have another reference to the woodyness of Grayshott, and Whitmore in particular, along with an introduction to the idea that it was an enclosed, or at least demarcated space.

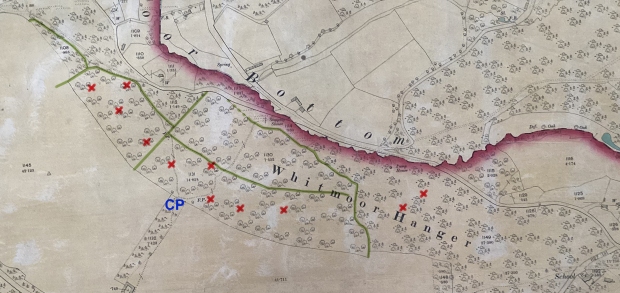

This map is from 1895. The medieval woodbanks have been highlighted in green. Almost all of them survive, except for the dotted portion at the very northern edge, which was largely knocked down when the meadow was made in the 1970’s. The corresponding banks on the farms were lost when the old fields were levelled in the second part of the 19th century, but they were integral with those of the wood. The charcoal hearths discovered so far are marked with a red X. The cross-path between Waggoners and Applegarth is marked by CP in blue.

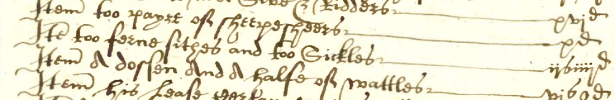

The bishops were enthusiastic bureaucrats, at least their scribes were, and from 1208 they kept detailed accounts of financial transactions within their manors. In Grayshott we find a few relevant entries.

– In 1543, John William was granted a plot of land 12 feet by 10 feet in the east of Headley (which Grayshott and Whitmore were) for a charcoal shop.

– In 1545 Richard Drake took out a rent on 2 1/2 acres of ‘moor and underwood’ ie coppice, in the south part of Whitmore.

– In 1556 John Warner was granted a licence to ‘move an exceedingly ruinous barn from Northland to Graveshot for the use of the woodwards’. A woodward was the guardian or keeper of the woods, acting on behalf of their owner, and John’s land was on the plateau directly above the hanger.

From the same era, 1552, we have a survey which describes the wood and waste (ie common land) in the area of modern Grayshott village. It tells us that ‘There is a wood of hethe and waste …. of which the wood contains 140 acres and the waste 103 acres’, and in passing mentions ‘the wood of Whytmore’.

From a survey made for the Bishop of Winchester in 1552. With a bit of squinting the words say ‘bosci de whytmore’ – the wood of Whitmore.

These paint a more detailed picture. We now have direct documentary evidence of woodland practice (coppicing), industry (charcoal making), landowner supervision (woodwards) in the general area, and best of all, specific mention of the wood of Whytmore. Added to this, we have the names, wills and inventories of a early 17th-century charcoal-making family, the Larbys, who we believe lived in Barford and quite possibly worked the hanger. Our full article on charcoal is on the New Finds page here. These provide the documentary elements for us to see the hanger as a pre-1600 managed woodland landscape, and extrapolating from the earlier data, to conjecture that it had been so for hundreds of years.

Moving on in time, we can look at the tithe map of 1846 and the subsequent enclosure map of 1855. Here we have beautiful hand-drawn maps showing the tree-filled areas within the medieval woodbanks. They’re named as Cane’s Coppice, Holloway’s Coppice and Beechen Row. The woodland outside the banks isn’t shown because it was common land, rather than tenanted, and therefore had no relevance to the financial purposes of the maps. But we know it existed – the map of 1826 shown above proves the point.

The tithe map of 1846 shows Cane’s Coppice (C), Holloway’s Coppice (H) and Beechen Row (B). The old coppiced flank of Flat Wood (FW) is discernible on the original by the use of deciduous tree symbols rather than the conifers to its west.

Archaeological Remains

Mention of woodbanks takes us towards the archaeological remains. We’ve already touched upon charcoal-making, and so far at least twelve potential hearths have been found. The hanger also contains hundreds of yards of earthen woodbanks. These are substantial structures, they would originally have been several feet from peak to trough, with a hedge on top. Building them – all by hand, dug out of rubble on a punishing gradient – was a huge effort and a token of the importance invested in the land they protected. They are integral with and therefore almost certainly contemporary with the farmed landscape on the plateau. Our current working theory has it that the farmscape was fully developed by 1208 – the year the Bishop of Winchester’s records start – possibly much earlier, and the woodbanks must therefore also be of that vintage. This physical evidence takes us right back to the time of the earliest documentary records.

It beggars belief that the valley slopes were farmed – it would have been physically impossible and totally unnecessary. Our hunch is that each farm was allocated a portion of flat land, nominally 10 acres, and a portion of the hillside. They grew crops on the flat and used the slopes as productive woodland. The products would have been coppice poles for construction, toolmaking and charcoal, timber for sale and heavy construction and scrap brush for firewood. We have an insight to this from the sale of High Graveshott farm in 1772 (roughly the land upon which Waggoners estate now stands). The price included an element of £50 (equivalent to about £8,000 in 2024) for timber and coppice wood.

Recorded in the sale of Keyne’s (ie Cane’s) estate in 1772 – timber and coppice wood worth £50.

There’s other archaeology too – an ancient road (Bull Lane), the shadows of old tracks, crumbling sawpits and the two Victorian ram pumps that were installed to supply water up to Grayshott Hall. Overall, humans have been at work in the hanger for centuries – digging, cutting, burning, foraging and poaching – and left witnesses to many of these in the woods and soil.

One of the ram pumps, installed in the 1870s – 80s to supply fresh water up to Grayshott Hall.

What Does It All Mean?

Putting all this together, we can conclude that the hanger is a cultural landscape which has a history spanning certainly centuries and perhaps millennia. Over that timescale nature has, of its own accord, ebbed and flowed. Species and dominance come and go – for example when windblows open up the canopy, disturb the soil and allow the ingress of new colonists. The principal biological continuity is probably the soil, which has gradually through the action of worms, insects, microbes and fungi turned leaf litter and deadwood into a rich, mycorrhizal growing mix. Trees come and go but the soil gets thicker and thicker. It’s a memory-bank of history which has yet to be scientifically interrogated.

Human activity has also had its ups and downs. Early exploiters probably used the woods as an infinite resource, cutting and taking in a way that was sustainable through its low impact. Over time, people noticed that certain practices caused the trees to grow better (coppicing and pollarding both extend tree lifespans), so exploitation turned into deliberate management. It probably reached a high point in the medieval and Tudor periods. The dilution of economic drivers in the 19th and early 20th century caused humans to take their hand off the steering, since when the woods have survived (and mutated) more or less on their own.

Disuse and Decay

Visiting the hanger now, it is obvious that however wild, beautiful and rich it is, it has not seen the hand of humans for many decades. Charcoal burning pretty much died out towards the end of the 18th century, when coke-powered blast furnaces of the midlands killed the Wealden iron industry. Coppicing declined through the 19th century as industrial goods took the place of woodland-craft products. Local timber production continued into the early 20th century, but the hanger’s terrain prohibited modern mechanical extraction and in any case the trees aren’t prime timber quality.

We think the hanger was last consistently and professionally managed in the 1920s under the squirarchy of Alexander Whitaker of Grayshott Hall. After his Wishanger Estate was broken up in 1927, the hanger became divided between several private owners, and the modern property lines paid no heed to the woodland’s historic boundaries. Without the influence of a single guiding mind the chance of coherent management dissolved. The evidence of the fantastically outgrown beech coppice certainly points to decades of neglect.

An incredible outgrown beech coppice, perhaps untouched for a century.

And what it would have looked like – hazel coppice at the top of Bull Lane. This was last cut circa 2017, and is nearly ready for a crop of hurdle poles.

We can walk through the hanger now, surrounded by nature, and on most days see not another living soul. A few hundred years ago it would have been teeming – at any time perhaps a dozen woodsmen, colliers and foragers would have been at work there, amidst manicured coppice coupes and neatly trimmed timber standards on the woodbanks. Exploiting its resources absorbed huge efforts of time and energy, and in return it provided our villagers with building materials, cash income, fuel and (we can hope they appreciated it) natural beauty, all of it sustainably and for centuries.

Looking To The Future

Trees have been around for about 400 million years. They grow on their own and have worked out how to get on without humans. But Whitmore Hanger isn’t just a collection of individual trees, it’s a wood, full of millions and billions and trillions of relationships between plants, animals, soil and climate; it’s not a stable ecosystem. We can walk through the hanger and it’ll seem a timeless wilderness, probably peaceful, certainly engulfed by nature; we can enjoy a lung-busting leg-stretch or sit on a log and think big thoughts, and within our timescale it seems like it’ll be that way forever. But it won’t. As a landscape whose composition, structure and biodiversity has been influenced by centuries of direct interaction with humans, now that the form of interaction has changed, the wood will change. The biodiversity of the hanger isn’t just a product of nature, it’s the story of humans’ relationship with nature.

Possibly the most obvious signs are the outgrown beech coppice – contorted, Rackham-esque creatures reaching their wavy arms up into the high canopy. They are striking, weird and rather feral. But if they continue to be neglected they’ll die and not be regenerated. Beech isn’t a long-lived tree – its maximum lifespan is 300 years and most tall-grown standards are dead by 200. It’s also accident prone – it has shallow roots and the fragile greensand subsoil and steep gradients make the giants of the hanger prone to windblow. Several have gone over in recent years. Without human assistance they’ll struggle to replace themselves.

Crash! The gnarly old veterans guarding the woodbanks are nearing the end of their lifespan. Behind, the holly is advancing and ready to make life difficult for their replacements. It’s always sad when one of them gets taken by the wind, but ….

…. life goes on. For trees, anyway. The dead wood feeds countless other species, from microbes to birds, and nutrients get recycled into the soil.

Lacking the hacking and chopping of old woodsmen, the hanger’s understory is becoming clogged with holly. Beech is one of the few trees that will germinate and grow in shade, but holly’s growth rate is equal to beech and it gives it a hard time. As the beech die out, holly might well take over and rather than open woodland the hanger will become a thicket. Being evergreen, holly casts shade all year long which that means that woodland-floor plants that rely on spring sunlight, such as bluebell and primrose, will be suppressed. It’s already happening.

Since 2022 the eastern 25 acres of the hanger (roughly the portion between the meadow at the bottom and the steep footpath down from Beech Lane) has been owned by the Woodland Trust. The Trust has been going since 1972, and they currently own over a thousand woodlands covering about 50,000 acres. A fair bit of this is ASNW or PAWS, much of it in decayed condition. The adjacent landowner has about 15 acres, and the Trust has leased its portion to them. Now, for the first time in a century, these 40 acres are in the process of being restored as part of a long-term and expertly guided plan.

This doesn’t mean that the hanger will be turned into a re-creation of a medieval working wood. That would be futile even if it was possible. The objective of restoring ancient woods isn’t to turn back the clock, but to develop a future woodland with improved ecological integrity and resilience. The historical remnants of an ancient wood are a link to the past, and they form stepping stones to a future which is different from the past but hopefully equally sustainable and diverse. This is especially relevant in the context of climate decay. The Trust is currently involved in the restoration of over 90,000 acres of ancient woodland, either their own or through support to private owners, so they have some idea what they’re on about.

It’s a three stage process, similar in principle to medical triage.

1. Halting further decline. In effect, targeted first-aid to stop further decline, protect what’s there and address safety issues.

2. Recovery of the wider ecosystem. This is the long-term activity of reducing lesser threats and progressively restoring the wider woodland composition.

3. Maximising ecological integrity. For example, succession planning for old trees by regenerating the veterans of tomorrow.

All of this takes years, lifetimes actually.

Whitmore at the moment is in stage 1. The priorities are to deal with safety hazards and get to work on light management. Unfortunately it’s impossible to undo a century of neglect overnight or invisibly. In practice this means a degree of felling, pruning and clearing the understory. Where big trunks need to be moved, horses are being used instead of heavy forestry machines, to reduce damage to the soil structure. The objective is to let more light onto specific trees and to the woodland floor. Hopefully the influx of spring sunshine will then pull into life the buried seedbank of groundplants that have been suppressed for decades, and give saplings the chance to flourish. Just like life-saving first-aid, it’s messy and perhaps unsightly work, maybe upsetting to witness. There’s chainsaws, heaps of cut brush, raw stumps and pushing the analogy a bit further, visitors sometimes need to be diverted.

But …. things will improve. The holly brush is being formed into dead hedges, which become refuges for birds and small mammals. Much of the felled wood is being left in place, to rot, recycle into soil and provide homes for billions of microbes, fungi, worms and insects, which in turn feed the birds and mammals. Bluebells appeared last spring and hopefully there’ll be more this year. We should also see baby beech trees emerging from the leaf litter. Given a chance, nature recovers quickly.

These newly made dead hedges would have been familiar to medieval woodsmen. Scraggy brash was used to keep herbivores off new growth and to demarcate coppice coupes of different ages.

The longer term remains to be seen. Heritage HQ isn’t aware of any solid plans but we might hope to see specimen areas of coppicing, perhaps some woodcrafts or educational foraging sessions, maybe even the occasional charcoal making adventure. Meanwhile, if you’re handy with a hatchet and would like to be involved in the restoration right now you can send a message to us here and we’ll facilitate contact.

Visiting The Hanger

There are a few ways you can enjoy visiting the hanger, of various energy levels, all on public rights of way, and which allow you to sample pretty much everything described here.

If you’re not particularly ambulant then you can just about visit by car. Head down Whitmore Vale Road, down the steep hill into the bottom, and you can usually pull over for a few moments onto a muddy patch somewhere before Purchase Farm. Leaving your car, you can walk along the lane (please take care not to get laminated into the tarmac by the frequent motorised maniacs that seem magnetically attracted to this stretch) and look up into the woods. The woodland here has a lot of alder, which is favoured by the constant flow of fresh water from the springs. Its shade nurtures mosses, fungi and lichens and the nitrogen-fixing characteristic of its roots helps to nourish nearby plants. In the foreground, the Southwater stream is recovering its course now that Trust’s tree-trunk barriers are preventing off-roaders from churning up the streambed. The stabilisation of this environment will help to encourage regrowth of bog-loving ground plants. Not particularly visible, but sensed by the lush green-ness further up, the waterlogged soil is home to some rare bog mosses. You can also see Grayshott Hall’s two ram-pump houses. It’s a lovely stretch of road from which to spend a few minutes gazing in to the woods, especially when the beeches have their bright green spring clothes or russet autumn colours.

For an easy, flat, buggy/granny-friendly walk you can start at the sports pavillion, from which head diagonally across the playing field towards the allotments, and make your way to the woodland-edge footpath. Turn left, and having admired the new community orchard, you can proceed past the heaps of flytipped garden waste behind Waggoners, and from there through the gate and onwards behind Applegarth. This path doesn’t go deep into the hanger, but you can at least peer down in. For added adventure, you can continue to the clearing at the top of Bull Lane, from which there’s a lovely view over the valley. Before returning you could venture on into Flat Wood, which is also very pretty.

If you have good legs, or at least boots, then from the previously mentioned clearing at the top of Bull Lane, you can walk down the ancient track. This instantly gets very exciting because on your right you’ll first of all see some splendid gnarly beeches upon the medieval woodbanks, behind which is Beechen Row. Downwards, the woodbank to your right all the way, you pass Holloway’s Coppice. Towards the bottom, behind an L-shaped beech tree, there’s a charcoal hearth. Before reaching tarmac, veer right before the works compound, and take the uphill footpath with a new post & rail fence on your left. Now you’re inside Holloway’s Coppice. You’ll cross a hump of woodbank, which takes you into Cane’s Coppice. Now, you’ll be puffing uphill, straight across another charcoal hearth, and emerge at the Applegarth crosspath. This is a good route if you want to see some of the restoration work, plus some smashing trees and easy archaeology.

Beautiful. The top end of Bull Lane.

A final suggestion, for now; from the Applegarth crosspath you can descend steeply through Cane’s Coppice and after about 30 yards take a yellow-arrowed path to the right, which crosses the hillside diagonally. After about 70 yards veer off left, straight downhill, keeping the green meadow to your forward left. Watching out for more yellow arrows, you’ll probably need to do a bit of bog-hopping across the flat bit, then descend through trees to the tarmac lane. En-route you’ll cross two woodbanks and maybe spot a saw-pit. It’s a good slither down to the tarmac by the watersplash. A quick paddle to clean the boots is always fun, then head uphill along the lane of Whitmore Vale. After a bit of a switchback this brings you to the bottom of Bull Lane, from which you can head back via either the footpath (turn left) or Bull Lane (turn right). This is a super little route if you’re sure-footed and feeling slightly energetic.

JC – February 2024.

… About Grayshott’s A-to-Z of Trade?

Whilst we were researching the Boundary Walks it became startlingly clear that olden-day Grayshott was an almost entirely self-sufficient community, in terms of the goods and services that traders offered to their local customers. Our 21st century needs are rather more diverse and complex than those of our predecessors and we all need to stray outside the village from time to time, but up until WW2 the village’s shopkeepers and artisans catered for virtually every day-to-day requirement of its citizens, and a few once-in-a-lifetime ones as well.

Some of Grayshott’s traders, from a Parish Magazine of 1949.

We thought it would be fun to compile a non-exhaustive A-to-Z of the goods and services that could have been obtained, and with the help of suggestions put forward at our October 2023 Friends’ Evening, here it is. We’ve disallowed groceries, because apple, banana, cucumber etc would be just too easy. And we’ve set an arbitrary end-date of the onset of WW2. We felt that after that watershed the relative commonality of daily commuting, specialist consumer goods and world-travel somewhat diluted the situation.

A

Anthracite, axe, accumulator, an auger, anvil

B

Bread, bible, bicycle, brassieres, bricks, black bananas (from Woods, we’ll allow that one because it’s fun), your baptism, bandages, beer, brandy, a broom (besom, of course), a bowler hat, butter, bacon, beef, books, boots, blankets, biscuits

C

China, corsets, confectionary, cod, combs, camera, chimney sweep, cakes, cider, crabs, cheese, chicken, a car, coal, coke, a clock, corn

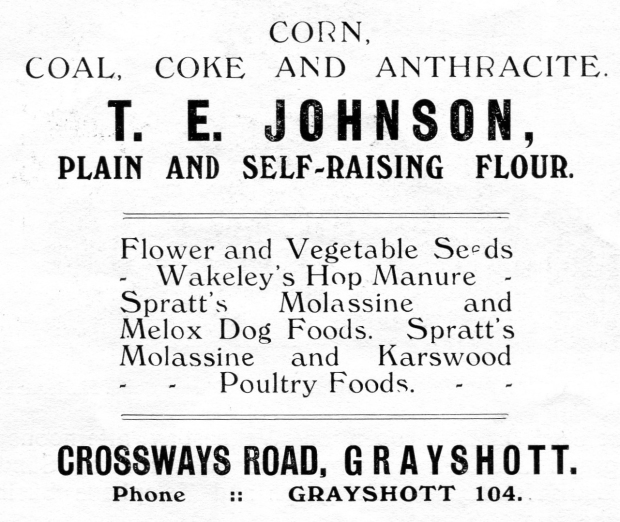

In 1926 Mr Johnson would help to keep your human and animal household warm and fed. His shop was on Crossways, next to Larcome the Butcher (now Amery vets).

D

Duck, drugs, drainpipes, dustbin, dog food, dolls

E

Eggs, envelopes, earthenware, ear trumpet, your education, enamelling, elastic

F

Fish, furniture, your funeral, flour

The Warr empire was founded by Fanny Warr circa 1900, and extended to four shops in Grayshott and another in Beacon Hill. Fanny died in 1915 and the business was continued by her children, here advertising in 1926.

Printed on a Fanny Warr brown paper bag. In the early 1900s she had three adjacent shops in Victoria Terrace, Crossways.

G

Gramophone, game, glass, gin, a goose, gobstoppers, gloves

H

Haddock, herring, hat, hosiery, horseshoes, a house, honey, hair cream, hammer

I

Ice, ice cream, ink, inner tube, Ingersol watch

In 1926 Owen and Son would keep you ticking.

J

Jugs, jacks (toy shop), jewellery, jigsaws, a jumper

K

Keys, knickers, K shoes, knives, kippers, knitting pattern

L

Linen, lemonade, lanterns, laces, liquers, lingerie, lamb, a ladder, liver salts

Every twenties flapper needed her gramophone, and in 1926 Phillips was the place to get one.

M

Motorbikes, marbles, mutton, milk, manure

N

Nuts (metal and edible), nails, newspapers, needles

O

Oil, oxtails, offal

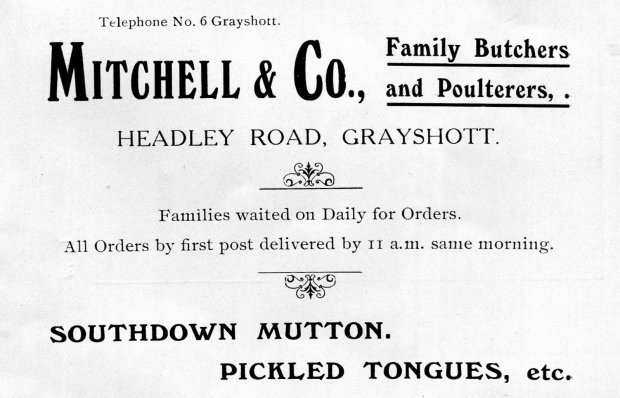

Mitchell’s, 1915. Still in the same business today, as Kaighin’s, as far as we know it’s the only shop in Grayshott that has continuously maintained its trade.

Woods – fishmonger, poulterer, game dealer – circa 1920. Note the delivery boy and his bike on the left – supermarkets’ home delivery is nothing new! In the left window hang bunches of black bananas, which is how they were preferred then. The canopy is still well preserved, as is the tiled frontage, although now hidden from view by modern grey paint. (It’s currently an accountancy office, opposite Frankie’s).

P

Paint, petrol, paraffin, postage stamps, postcards, a photographic portrait (2 points for that), paper, a pheasant, pickles, pills, pickaxe

Q

Quinine (we’ve checked, and yes the chemist sold quinine), a quilt, quicklime

R

A radio, a rake, rope, rivets, a razor, raincoat (Burberry), rare drugs, records

Until recently The Pharmacy in Headley Road (now Homes), Harrison’s chemist shop offered something for all the senses.

Harrison’s in the snow, 1930s. It originally had a fancy glass globe light suspended from the iron bracket over the door, but now gone AWOL.

S

Sausages, stationary, a saddle, a suit, spirit level, smelling salts (2 points again), snuff, shoes, socks, a shirt, spark plugs, scissors, seeds, spectacles

T

Tobacco, taps, tacks, a telegram, trousers, turps, a turkey, tongs, talc, tyres, trowel, thread

U

Umbrella, underware

Proprietor Oliver Chapman was also the church organist and a founder member of Grayshott Cricket Club. 1903.

V

Varnish, a vase, Vaseline, vulcanised tyres, venison, the vet (at 11am on Tuesdays and Friday at Wells the blacksmith), a vest

W

Wine, whisky, a wardrobe, watercolour paints, writing case, wreath, wire, your wedding

X

A xylophone (from the toy shop), an X-Ray (very briefly, on 28th December 1898 from Dr Plimpton)

Coxhead and Welch catered for the pioneer motorists and DIY enthusiasts, 1905. An Aladdin’s cave, they were still in business a hundred years after this advert, but very sadly no longer.

A magnet for men in flat caps – Fred Harris’s shop circa 1928. He had another branch in Liphook.

Y

Yarn, a yo-yo, yeast

Z

Zinc bath, a zip

George Cornish had his grocery shop in Hindhead Terrace, opposite the pub. This advert is from 1926, he was still there in the fifties.

JC, October 2023

… About Latin?

We don’t, not much anyway, but we’re intrigued about the glazed tile panel in the porch of Marathon on Headley Road (next to Frankie’s Fish & Chips).

The tiled panel in the porch of Marathon, Headley Road.

Our committee intellectual, Archivist Martin, tells us that it’s from Psalms 91:10 and translates as ‘There shall no evil befall thee, neither shall any plague come near thy dwelling’. Let’s hope it worked during Covid.

The building was originally one of Madame Fanny Warr’s shops. She had four in the village at one time, dealing in ladies’ and mens’ wear, shoes, stationary, art materials, toys, books and a lending library. We really have no idea as to the relevance of the words to Madame Warr, her businesses or the property, and any suggestions to that effect are welcome.

JC, June 2023

… About Coronations?

With the imminent coronation of King Charles III in mind, we thought to review village festivities for previous royal enthronements. Grayshott was formed as its own civil parish in 1902 and has celebrated four coronations.

1902 – Edward VII and Alexandra

1911 – George V and Mary

1937 – George VI and Elizabeth

1953 – Elizabeth II

The 1902 event was written up in the Grayshott Parish Magazine and it sounds a grand affair, with a thousand-guest tea party, sports and games, a donkey race, bonfire, competing brass bands and a downpour. One of our favourite correspondents, Mrs Cane of Stoney Bottom, entered her donkey which unfortunately came last. The full report is here and it’s a surprisingly fun read.

Mrs Cane’s donkey, a runner in the 1902 festivities, photographed here several years before the event.

1911 seems to have been rather more muted, and as far as we can find was limited to Granny Robinson planting a yew tree on Lyndon Green. It’s still there, an Irish yew, taxus baccata Fastigiata.

Granny Robinson admiring her tree, 1911. We suspect that like all such good affairs, somebody else dug the hole. Note the fireman behind, restraining the crowd, who, in their best day-out hats, mostly seem to be looking the other way.

In 1936 Edward VIII came and went in a froth of publicity but without hanging around for a coronation, which saved everyone a fortune.

Then, in 1937, came George VI and Elizabeth. The Aldershot and District Traction Company decorated one of their latest Dennis single deck buses. Some 850 red, white and blue lamps were used, along with an illuminated crown above the cab, plus 700 coloured beads that showed through when lit up from the inside. Ooooh! Music was transmitted through a loudspeaker while the vehicle toured the company’s territory. No doubt it came through Grayshott at some point.

The 1937 Coronation Bus. We wonder if the Stagecoach Number 23 will make a similar appearance this year?

Finally, in 1953, for our Queen Elizabeth II there was a hectic programme of church services, tea parties, fancy dress, whist drive, social evening, a dance and another bonfire. The full programme is here.

This year’s village event promises lots of live music, children’s games, heaps of food and no doubt a little drink or two. But for donkey races, illuminated buses and a good burn-up we perhaps need to learn some lessons from history?

JC, May 2023

… About Grayshott’s Heaths?

For most of us the heaths that surround our village are an everyday part of life, something that we see every time we walk, cycle or drive more than a few hundred yards. There’s no escaping them – Ludshott Common, Bramshott Chase, Devil’s Punchbowl, Hindhead Common, Frensham, Hankley, Thursley. These areas, technically know as Lowland Heath, are in fact an internationally rare and endangered environment. They host many rare plants and animals which have adapted to their combination of low fertility, aridity and human exploitation. All of those places just mentioned are part of the Wealden Heath Phase II Special Protection Area, which recognises the need for their careful management and protection. Those responsible for doing so have to balance the opposing forces of conservation, recreation, urbanisation and budget. Thankfully Grayshott Heritage isn’t one of those organisations!

Heaths and commons are not the same. ‘Heath’ is the term for a specific environment, which in the lowlands (less than 300m, as we are) is characterised by sandy, infertile soils hosting vegetation dominated by heather, gorse and coarse grasses. ‘Common’ is the term for land over which people have, or had, rights of access and use, that is, ‘land of the community’. In medieval times the lord of the manor had to provide sufficient unfenced land to supply the needs of the manor’s commoners. In our area it just so happens that most heaths are commons and visa-versa.

Every heath has its own history, but in general they are ancient creations. After the last glaciation, about 11,000 years ago, Southern Britain became covered first by steppe, then by forest of birch, Scots pine, hazel and oak. Farming became established around 6,000 years ago. The early farmers were industrious people and through centuries of backbreaking labour much of lowland Britain became deforested. Very, very gradually the population increased and people had to look for new land, which tended more and more towards marginal areas. Luckily for them, at the same time the climate improved noticeably and by about 3,000 years ago it was viable to farm up to altitudes of about 400m. For reference, Grayshott village is at about 200m. The presumed scenario hereabouts is that the earliest farmers initially ignored our ridge but, little by little, their descendants pushed their farms up the slopes, a rising tide of fields replacing forest. According to this model, Bronze Age farmers were nurturing their livestock on the plateau where many of us now live, albeit perhaps as not much more than range-style pasture. Some evidence towards this model are the Bronze Age burial mounds, barrows, still visible at places such as King’s Barrow Ridge (Frensham), and much less so on Ludshott. It’s been proven by pollen analysis that barrows were almost always made on open land, often grass pasture, where they could be clearly seen from a long way off. A small Bronze Age settlement has been found at the far side of the Punchbowl, so we know for sure that people were living around here at that time.

The good times didn’t last though. Through the next thousand years the climate worsened, it became cooler and wetter, and the upper limit for agriculture reduced to about 250m. Our optimistic colonists were faced with a double-whammie – Grayshott is on the Hythe Beds of the Lower Greensand rock, which is the least fertile of all, plus we have an altitude-related cooler and wetter microclimate. Gardeners will know that our spring comes two weeks later than Churt or Headley. This led to the greensand ridge being abandoned. The probably situation is that by about 2,500 years ago, locally, the farms had retreated to the river valleys and our higher ground was used as summer grazing.

Two maps, below, show graphically the combined effect of bedrock and altitude. On the geological map, our Hythe Beds are the pale green area, with Grayshott village at the centre of the map. Most of this, except the steep scarps and valley sides, was most likely farmed or at least cleared for pasture to some extent in the later Bronze Age. The surrounding purple and grey areas are Bargate and Sandgate Beds, which are significantly more fertile. They form a C shape, enveloping the western end of our ridge from Churt, around Barford, Headley and Bramshott, and are farmed nowadays. Beyond the Sandgate, the khaki colour represents the Folkestone Beds, which are nearly as infertile as the Hythe, giving rise to Frensham Common.

A geological map shows how the Hythe Beds of Grayshott, Hindhead and Ludshott (pale green) are enclosed by rims of Bargate (purple) and Sandgate (grey) Beds.

The first edition Ordnance Survey map, below, shows clearly how the farms follow the geology. Grayshott village didn’t exist when it was originally surveyed (1808), and the old farming hamlet is shown by the white area in the middle. They’ve called Ludshott Common Grayshott Down. The grey shading all around shows heath and woods. Beyond is the C-shape of cultivated fields, and beyond that again is another rim of heath and wood around Woolmer and Frensham. The old fields stop at the transition from Bargate to Hythe. You can see this yourself at the far end of Hammer Lane. Most of Hammer Lane is fairly level, with plantation woodland either side. As the road dips it becomes sunken, due to the softer nature of Bargate, and from this point the lane is bordered by fields. Those old boys knew that there was a certain line beyond which it was diminishing returns to persevere with scratching away on the higher ground. A pre-excavation archaeological report for the Hindhead Tunnel went so far as to suggest that the pattern of small, dispersed farmsteads around the Hythe Beds’ rim may be the fossilisation of a pre-Roman landscape, the ‘low-tide’ following abandonment of the higher ground.

Exactly the same area as the map above, this old OS map clearly shows how pre-industrial farmers left the poorest soils as heathland (the grey areas). The fields almost exactly follow the curl of the more fertile Bargate and Sangate Beds.

This climate-driven retreat of agriculture set the scene for the development of heaths as we know them. Removal of the tree cover would have accelerated the rate at which rainfall leached away remaining nutrients and washed away topsoil (a lesson that some modern farmers are still to realise). The sand heated up quickly in summer, became parched, and in winter cooled quickly. When the farmers moved out, hardy, drought tolerant plants such as heather and gorse moved in, although trees were kept at bay through continued livestock grazing. In some places an impermeable iron-pan formed, leading to localised bogs.

Some time early in the medieval period, for reasons proposed in another article here, a small farming settlement grew up in the area to the west of the modern village. It was a ring-fenced hamlet on the plateau, a green enclave surrounded by heath, like a monk’s haircut. In those days the area of the modern village and the Land of Nod were commons.

A survey of 1552 has this to say: ‘There is a wood of hethe and waste being in a wood containing 240 acres, lying in length on the east part of graveshotte, in length between kingeswodd bottom on the south part and graveshotte and sturley dene on the north, and on the west abutting upon brokesbottom, and on the east abutting upon les marke okes, of which the wood contains 140 acres and the waste 100 acres.’ This is the area of modern Grayshott village. In this context the word ‘waste’ doesn’t have the modern meaning of rubbish or surplus, but derives from the Latin vastus – empty or by extension, uncultivated. Furthermore, ‘There is another waste containing 100 acres, lying on the east part of Hethelehyll and …. reaching towards graveshotte.’ This, roughly, was Land of Nod.

Part of the 1552 survey, describing the heaths – ‘vast’, meaning waste – around Grayshott.

And so it was for a thousand years or more.

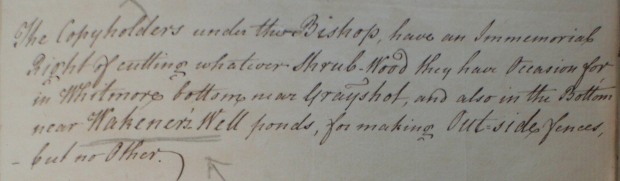

The villagers of this hamlet, Graveshotte, had commoners’ rights (so long as they paid their rent – squatters had no official rights). These rights formed part of the customs of the manor, a set of rules understood by everyone, which had been agreed since time immemorial and held in the collective memory. Occasionally they were written down in a custumal, as happened for Headley in 1766. These rules set out the parameters within which the villagers could exploit the commons, or heaths. They were valid until the Headley Inclosure of 1855, at which point the rights were withdrawn and the commoners awarded compensation in the form of land or cash.

A few examples as to what our villages could use the commons for:

– Grazing livestock, of a number proportional to the size of their property.

– Collecting deadwood, but not standing trees.

– Taking minerals – stone and sand for example.

– Collecting turf, bracken and gorse.

– Collecting food (nuts, berries) and herbs.

– In Grayshott, collecting shrubwood ie coppice for making fences.

There were limits. For example, your rights only applied in the manor to which you were a tenant. Pilfering from another manor’s waste was fineable. The boundary between Headley Common and Ludshott was marked by a large ditch and bank, so there was no excuse for not knowing when you’d strayed off home soil. Also, standing trees were deemed as timber, the lord’s property, and felling without permission was – guess what – fineable. Manors employed officials such as pinders and woodwards to enforce the customs.

By the 19th century the heaths in our area were under the pressure of enclosure. As marginal agricultural land they were seen as having little potential for the emerging industrial farming; their value lay in three things – the army, building and forestry. Part of the reason that the army chose Aldershot as a major base in the 1850s was the availability of thousands of acres of ‘useless’ heaths which they could requisition as training areas. Ironically, having removed the land from commercial use, the army’s heaths are now some of the best preserved remainders. Even though, in WW2, the Bronze Age barrows on Frensham were used as targets for mortar practice…. The other pressure, still into today, was urbanisation. The prospect of large expanses of cheap, well-drained land was a builder’s dream, and was actually the driving force behind the enclosure and sale of Grayshott’s heaths. Meanwhile, good quality timber had been scarce for centuries. Even in the 17th century the Weald was becoming dangerously deforested by the iron industry’s demand for charcoal, and the Navy’s appetite for timber was insatiable. By 1800 local landowners were turning heaths into coniferous monocultures, an investment for their heirs.

The beginning of the end for many heaths – new houses on Headley Down, 1912. Courtesy of Jo Smith.

The survivors of these forces are now the relatively tiny fragments around our village, luckily now all recognised and protected. In the late 19th century Victorian visitors arriving into Haslemere by train ‘discovered’ the wild scenery, fresh air and picturesque local denizens, and quite a tourist boon ensued. Fortunately, this led to the area’s beauty and fragility being recognised and much of the heathland was acquired by the National Trust. Recently the Heathlands Reunited project is attempting to restore and reconnect the islands of heath within the South Downs National Park into a larger, more coherent and less vulnerable ecosystem. They need to be looked after because new threats to their existence have emerged. Without livestock grazing, trees quickly take over. Controlling tree cover is one of the biggest headaches of heath management. The other is recreation; these once remote wildernesses now sometimes look more like Regent’s Park on a Sunday afternoon

Finally, here is a non-exhaustive list of some of the harvest that our predecessors derived from the heaths.

Birch

Birch trees are wonderful things. They’re a pioneer species, one of the first to move in after the glaciers left, their tiny seeds able to travel far and wide on the wind and lodge in the tiniest nooks of cover. For 10,000 years they’ve been making topsoil. Their roots penetrate into the subsoil and bedrock, drawing nutrients up into the leaves and wood. The leaves being friable rot down quickly in autumn, and the wood itself is quick to decay. Through this cycle they quietly work away at turning rock into soil, and are beautiful as a bonus. A birch will be ready to fall at 70 years; the ones we see around us every day are the many times great-grandchildren of the first arrivals.

Birches have been around for about 50 million years, which is 49,700,000 years longer than humans. But in our relatively short relationship with birch we’ve found it useful for many things. The wood isn’t much good for building – it’s strong but not durable – but it’s easy to make into little utensils such at plates, bowls, spoons, spindles and so on, all of which our commoners would have knocked up at home in their spare moments. The bark is waterproof and can be made into pots and buckets, or cut into withies for basket making. We all know that the broomsquires used birch twigs for their brushes. The sap is drinkable, like sugary water. In spring it’s possible to tap and collect it, and make it into wine.

In his 1664 book ‘Sylva’, John Evelyn proposed this recipe for birch wine. If anyone would like to have a crack at it and bring some to a Friends’ Evening for tasting, we will be delighted to send you the insructions for tapping the birch water!

Scots Pine

Another post-glacial pioneer, the jury is out on whether like birch, the ones here are natural survivors from that time. Some studies seem to show that the pine forests of southern Britain were displaced by deciduous and that the pine only returned as a result of human agency in the 17th century, for plantations and gardens. This is not a concrete conclusion though, and whether or not it’s true they are a very handy tree for foraging commoners. It can be tapped for resin, rope can be spun from the inner bark, tar boiled from the roots and dye from the cones. By the 19th century it was well established as part of our heathland scenery and its eerie, contorted silhouettes amplified the wilderness appeal for tourists.

Holly

Holly, although not specifically a heath plant, in fact grows rather too well on them. In olden days it was cultivated in special enclosures called hollins and the smooth upper foliage was a nutritious livestock food.

Gorse

Gorse, or furze, was surprisingly valuable, to the extent that it was even cultivated from seed as a crop by farmers. The young tops of two or three years were succulent enough to use as animal fodder. The whole plant contains oils, so it burns hot and clean. The tops, dried, were used by households for cooking and heating fires. As it burns fast with little ash it was useful for bread ovens. The stems and roots, denser, were saved for more industrial uses such as brick kilns, where fierce heat was needed. Furze roots return nitrogen into the soil so it was also used for boosting the fertility of tired fields.

Furze – a source of fodder, fuel and fertility.

Bracken

Animal bedding, domestic fuel and thatch all come from bracken. Young fern is rich in potassium, and was burned to produce potash, as a fertiliser and for soap making. We’ve found fern scythes mentioned in the wills of two old Grayshott residents, and in 1458 the manor court of Ludshott heard that ‘John Langford of Grayshut cut and carried away one cart-load of wood and one of bracken from the common land of the Lord’s tenants without permission’. He was fined 3d.

The inventory of William Rapson, 1601. ‘Too ferne sithes and too sickles’.

Heather

Outdoorsie Victorians flocked to admire the mile upon mile of undulating heather, stunningly lovely even on today’s less expansive remnants. It could well be claimed that heather, along with its adjacent pleasures of walking and painting, charged the local tourist boom that stoked up the economic growth of Hindhead and Grayshott. In her book Heatherley, Flora Thompson expressed her character Laura’s reaction thus:

Pale purple as the bloom on a ripe plum, veined with the gold of late flowering gorse, set with small slender birches just turning yellow, with red-berried rowans and thickets of bracken, the heath lay steeped in sunshine. The dusty white road by which she had come was deserted by all but herself, and the only sounds to be heard were the murmuring of bees in the heathbells and the low, plaintive cries of a flock of linnets as they flitted from bush to bush. From where she stood she could see, far away on the horizon, a long wavy line of dim blue hills which to her, used as she was to a land of flat fields, appeared to be mountains. The air, charged with the scent of heather and pine, had the sharp sweetness of wine and was strangely exhilarating to one accustomed from birth to the moist, heavy, pollen-laden air of the agricultural counties. She stood as long as she dared upon the edge of the heath, breathing long breaths and gazing upon the scene with the delight of a discoverer…..

Lovely.

For the commoners, heather’s value was in brooms, booze, building and bees. As an alternative to birch, it made slightly inferior but cheaper besoms, as related in our article about broomsquires. In the absence of hops it was added to ale as a preservative. For building, it could be used as thatch, and around here, with no great source of reeds or long straw, it may well have been the normal material. And its pollen made rich, caramel flavoured honey (and still does!) All of our old villagers kept bees; honey was their only source of sugar, and of course the wax came in handy around the house and farm. In his will of 1543 John Grassett Senior left a total of 18 hives of bees to various family members.

The will of John Grassett, 1543, who among other things left ‘xii hyves of bees’ to ‘margarett my wyfe’.

Turf

The word suggests grass, but turf was actually the matted roots and ground litter of heather. It’s an excellent example of the inter-dependence of human activity, because the best fuel turves came from short heather, which itself arose from livestock grazing and cutting for brooms. When one activity stopped, others became compromised. The turves were cut in early summer and dried in special turf houses – open-fronted sheds – for burning through winter. Turf didn’t burn so much as smoulder. The cottagers would have kept a turf fire smoking away all the time. Wood was far to valuable to burn, except for deadwood picked from the ground, so to create instant heat they piled on some bracken or gorse.

In a pinch turf could also be used for building walls and roofs. To do so was a last resort of the desperately poor. We’ve not found evidence of it locally, but there are records of turf-built houses further east on the Surrey Heaths.

Coppice

Our commoners were allowed to cut coppice wood, or shrubwood as it was called, in certain places. It had a multitude of uses – hurdles, fences, tools. Coppices on the heaths had to be protected from the destruction of grazing animals, so they would have been fenced. The inventories of our old farmers almost always contain woodsman’s tools such as bills and hatchets, and their products in the form of ‘wattles’, meaning hurdles.

From the manorial custumal.

Food and herbs

Nuts, fungi and berries were free for all, as were herbs such as Sweet Gale. Sphagnum moss, from the boggy bottoms, was gathered for nappy padding and wound dressings. It’s now known to have anti-microbial properties. Locally, whortleberries or hurts were a late-summer treat, little purple-black berries which could be eaten straight, or made into preserves and jams. Some cottagers such as Stephen Boxall of Stoney Bottom managed to accumulate enough to go hawking them in Guildford and Godalming. A contemporary said of him ‘He had a tremendous voice and his cry “Ripe Hurts” could be heard a great distance.’

Hurt flowers in May. They’re becoming shaded out by trees but still proliferate in clearings.

Minerals

Our villagers could lift minerals from the commons for improving their soil and homes. In effect, this meant that along with their other rights they could almost build a modest house using materials to which they were freely entitled. Chalk could be burned into lime using fire from gorse. The lime added to sand would make mortar to bind the local rubble into walls, the like of which you can still see in plenty of village houses. Heather or bracken would cover the roof, although in the 15th century the lord of the manor required that roofs be tiled. The major exception was structural timber, which could only be felled with the lord’s permission and had to be paid for. No doubt plenty such was recycled or obtained nocturnally – timber theft was a popular village sport.

No need for a builder’s merchant when you could pop out on to the heath with a wheelbarrow and collect your own ingredients.

Livestock Grazing

The right of pasture was our villagers’ lifeline. Almost all of their fields, right up to the 19th century, were arable. In the medieval and Tudor periods their cash crop was sheep, for wool, milk and manure. At this time the fields grew oats and rye, the crops of poor soil. Rye was for bread, and oats for animal feed and porridge. The sheep grazed by day on the heath, and every night they were brought in to fold upon the fallow fields, to deposit their manure overnight. In this way there was a continual transfer of nutrients from the heath, via the sheep, onto fields. The sheep were nothing like today’s big, furry white pom-poms. To our eyes they would look poor, scraggy little things with dark, short-stapled wool, somewhat like the rare breeds one sees at shows. They were adapted to rough living and known simply as ‘heath sheep’. There was a formula; it took two or three heath sheep per acre of arable to maintain its fertility, along with other sources such as wood ash and the domestic midden. Our farmers had the required quantity; Robert Luckin with 21 acres had 66 sheep, and Elizabeth Warner with about 60 acres had 135. The system worked, for hundreds of years.

Our villagers earned their wealth, such as it was, from little sheep like these. Wool for cash (with some kept back for knitting their own clothes), milk for cheese and manure for the fields.

Without the heaths this economy could never have functioned. Our villagers’ modest farms and smallholdings couldn’t have produced enough to live on and trade with without their right of pasture to the hundreds of acres of surrounding common land. The heaths were human-made, the result of early agriculture and climate decay, and became interdependent with their humans through a delicately balanced form of husbandry. Without one, the other couldn’t survive, and when the connection was broken they generally didn’t.

When visiting the heaths today one is most likely to encounter other walkers, cyclists riders and the occasional fly-tipper or arsonist, but quite often you’ll have the view to yourself. Turn the clock back and they would have been seething with activity – upwards of 200 sheep munching away, with their companion cattle, oxen and a few pigs, plus an assortment of turf-cutters, wood-gatherers, stone-collectors, bracken-harvesters, furze-clippers, berry-pickers, birch-brewers, broomsquires and trillions of insects and birds. We are very lucky to still have them on our doorstep, to enjoy freely whenever we like.

JC, December 2022.

… About lidar?

Lidar, or more properly LiDAR, is the acronym for Light Detection and Ranging. In its basic form it’s a method of measuring the distance to an object by pointing a laser at it and measuring the time it takes for the reflected light to return to the sensor. It has lots of uses, but as far as we’re concerned here it’s been developed into a system of airborne scanning which can generate highly detailed and accurate maps of the earth’s surface.

An aircraft fitted with an eye-safe laser flys back and forth across the landscape. The time taken for the laser pulses to make their round trip from the aircraft to earth and back is converted into distance, from which a map of the surface can be generated. It has two great advantages. First, it is much more accurate at measuring height than traditional maps. Second, because the laser beam is very narrow, it can usually see through vegetation and measure the land surface beneath trees, which normal photos can’t do. A recent project called Secrets of the High Woods has used Lidar to discover hundreds of new archeaological features on the South Downs of West Sussex and eastern Hampshire.

Some Lidars have an accuracy of 30cm, which means they can detect lumps and bumps in the landscape that are invisible from ground level, unless you know exactly where to look. A Lidar map doesn’t tell you what a feature is, but it shows up areas of interest which can then be explored in more detail on the ground.

We have just obtained Lidar images of the Grayshott area, which we show here. Each image is shown with its corresponding normal aerial photos, so hopefully you can make sense of them.

First off, a general view of the Grayshott area.

An aerial photo of the Grayshott area, the village centre in the middle of the picture.

Here you can see the built-up area of Grayshott village right in the middle of the photo. The A3 comes in from the top right, dissappears into the Hindhead Tunnel, emerges towards the centre of the picture and then out at the bottom left towards Petersfield. Ludshott Common is the brownish blob at the left of centre. It’s easy enough to pick out woods, fields, roads and villages, but the lay of the land isn’t at all obvious

Now, if you look at the same area in Lidar, below, the red letter G marks the junction of Crossways Road and Headley Road. Above it, Whitmore Bottom and Golden Valley (which in olden, less romantic days was called Diggens Bottom) join at the point W, which is in the area of Purchase Farm. Then moving clockwise, D is the Devil’s Punch Bowl, K is Kingswood Firs, WW is Waggoners Wells and L is Ludshott.

The same area as a Lidar image.

This view shows just how sharply the greensand ridge has been eroded into a web of steep, narrow incised valleys. Walkers and cyclists will know that the last mile or so home to Grayshott is always uphill! The little streams all flow into the Wey, then the Thames. In the late 19th century Grayshott village was made on one of the best local building spots – flat land, open to sunshine and fresh air, not quite high enough to suffer the worst gloomy drizzle of ‘Hindhead days’, and available cheaply after the Enclosure act of 1859. No wonder that Victorian builders chose it for a ‘new village’.

Next, in close up, the playing fields.

The playing fields, with Waggoners estate to the left and Beechanger area to the right.

We all recognise it; the playing fields, with the diagonal square of the cricket wicket in the middle, the tennis courts to the right, Waggoners estate to the left, and the woods of the Hanger beyond.

In Lidar, we can see something very interesting. The wicket, W, is obvious, as are the tennis courts, T. But, can you see the diagonal lines running across the field by the top of the wicket, and vertically from its top left corner? These are the old field boundaries from the days when the north-west part of the playing field was farmland.

The playing fields as a Lidar image.

If you look at the Tithe Map (below) you can see the old fields plotted on these exact lines. The five-sided area maked RC was called Rew Corner. Rew is from the Old English word ruh, which means rough. Hence the field name, as you might expect from its position at the extremity of the farmland, reveals that is was cut out of former heathland. We don’t exactly know when this happened, but possibly some time shortly after Sir Thomas Miller aquired the farms and started to improve them, so around 1800. Then, to the left, ‘LFA’ indicates the field of Lower Four Acres, now underneath Wheelwrights Lane. UK marks Upper Kiln Field, now Horseshoe Bend.

These old boundary banks and ditches were knocked in after Alexander Whitaker gave land for the playing fields to the village in 1919. No doubt his workman thought they’d made a good job of levelling the field, but Lidar shows differently. You can still just about see them now, especially there is a visible hump of the old bank between Rew Corner and Lower Four Acres when looking over towards the allotments.

Finally, the orange road running immediately next to the fields was the medieval ‘high street’, Graveshott Lane. Its remnants can be seen elswhere in the village, but not quite on the playing fields.

The 1846 Tithe Map of the same area.

And nearby ….

The photo below shows the Hanger immediately north of the playing fields (centre), Waggoners (left) and Beech Lane (right). Whitmore Bottom curves across the top of the picture and the green fields of Purchase Farm can be seen at top centre.

The Hanger north of the playing fields, Beech Lane and Waggoners.

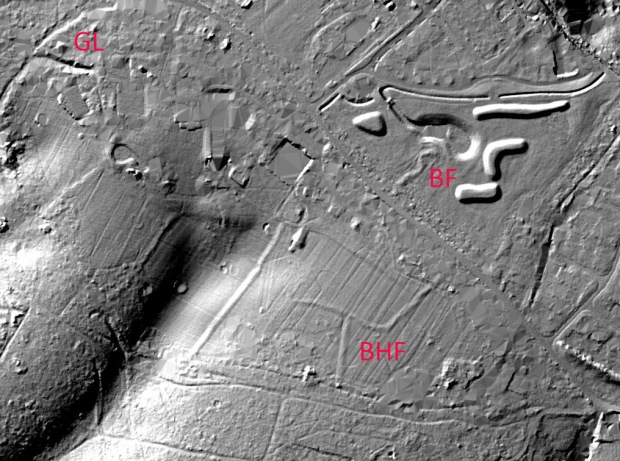

The corresponding Lidar image (below) is full of interest. The paler band running acoss about a third of the way up is the ancient woodland on the steep part of the valley side. Above it, most obvious in the centre, is the steep scarp of the spring line and the bluffs between the several little springs. Within the woods there are at least seven roughly circular features. These are charcoal burning hearths, as we wrote about in our feature here. Numbers 1-6 we had already found; number 7, if verified by inspection, will be a new discovery. It’s quite disorienting in the woods to try and understand exact positions, but here you can see how they obviously run in a line some way below the valley’s top lip. Not quite shown on the Lidar, but just about possible to trace on the ground in places, there is the ghost of an old track linking some of them together.

We expect that closer examination will confirm and reveal other features, such as the woodbanks that surrounded the old coppice, and saw pits. Unfortunately the tadpole shaped thing above number 7 isn’t a Norman motte & bailey castle or a prehistoric henge, but a modern workman’s yard, although the diagonal lines to its right look interesting.

The Lidar image shows the spring line scarp inside The Hanger, and several charcoal burning hearths.

And now to the area of Grayshott Hall.

The air photo below shows the buildings of the old hall and modern spa just above and left of centre. Below them, the hall’s old landscaped gardens are now a golf course, and at the bottom of the photo are the woods and heath of Ludshott Common. In the top right, on the opposite side of Headley Road, is the new estate of Applegarth Vale and the green space of Applegarth Meadow. Note and remember the short row of trees jutting into the meadow at right angles to the road.

Grayshott Hall and Applegarth Meadow.

Now the Lidar picture, below.

At top left, marked by GL, are some ancient roads. The one which cuts the corner diagonally is the bridleway which runs between Grayshott Hall and the house of Dunelm. In 1552 the people of Grayshott called it Barnfield Lane. Twenty years later the people of Ludshott called it Farnham Way, which is interesting because they obviously saw it as part of a longer distance road rather than just a local track. It was quite possibly part of a fairly busy route connecting the two wool market towns of Petersfield and Farnham. The track coming off it towards the right is the sunken lane of Graveshott Lane, which in the middle ages was the nearest thing we had to a high street. It’s on the private land of Grayshott Hall so you can’t walk along it, but you can see it from the bridleway. From here it ran across the front of Grayshott Hall towards Waggoners Bend, then through Waggoners estate, the playing fields, and Beech Lane. It’s far end is the little stump of School Lane which dives down into Whitmore. You can see these roads on the Tithe Map below.

The Lidar image of the same area shows the remains of medieval lanes and field boundaries.

Now, have a look at the area above and left of the marker BHF. Compare to the Tithe Map below and you’ll see some traces of medieval field boundaries. They’ve survived two re-landscaping events, first when Alexander Whitaker turned the fields into his garden, then when the golf course was made. Like the playing field, these are almost invisible on the ground, but very definitely still present. BHF was called Burnt House Field. It’s the site of the medieval farm of Home House. A wonderful map of 1739 (below) shows the house prior to its demise. Unfortunately the Lidar signal around its side is pretty ropey, probably obscured by dense evergreen foliage, so its no help towards finding an exact location.

Next, have a look at the top right corner of the Lidar. The kidney-shaped hollow and the wormy things are the modern pond and spoil heaps of the Applegarth estate. To their right you can see a dark line, which is the footpath running between Bailey Scott Cottage and Waggoners, to The Hanger. At the Headley Road end it preserves the line of the intake towards the medieval farm of Highe Graveshotte. This was later called Cane’s Farm and you can see it on the 1739 map. Unfortunately there is no sign of the surface of the farm buildings. By the way, the square and rectangular areas you can see on the Lidars are usually gardens, or where the image processing has removed buildings.

Finally, look at the little wiggle to the left of BF. Compare this with the Tithe Map below. This field boundary marks the site of medieval Barnelands Farm. The field to its left was called Water Hall Field. Hall means hollow – there was a dew pond in it. The outline of the pond is preserved in the kink of the boundary. Look at the intake to Cane’s Farm next door and you’ll work it out. Barnelands was derelict in 1552; the land was still farmed but the building was probably deserted as a result of the Black Death. At some point the pond silted up and the intake was absorbed into the adjacent field, leaving the peculiar, irregular outline. The farmhouse would have been at the far end of the intake. Nowadays this area is exactly under the short stand of trees perpendicular to the road that you saw in the air photo. We’ve known about this site for several years, but the correlation between the Lidar and air photo as proved without doubt that the trees coincide with the farm. These trees are not that old, probably planted by Whitaker around 1900. Our theory is that the land here is full of old rubble and rubbish from Barnelands. Perhaps the crops didn’t thrive or Whitaker’s ploughman got fed up of bending his blade on lumps of foundation stones, so the trees were planted as a ‘keep off’ warning. Nowadays you don’t have to keep off, Applegarth Meadow is a public open space, beneath the trees is alive with wild flowers in spring and a lovely place to pause for a few minutes.

The Waggoners Bend area in 1739. The to-be-burned house is on the left, Cane’s at the top.

Lastly for the moment, we’ll have a look at Flat Wood and Bulls Farm. This area either side of Hammer Lane was Grayshott’s foundation settlement, with Bull’s Farm at its centre and the fields radiating from it. In the 16th century Flat Wood was fields, called Old Land, which when it occurs as a placename is taken to mean a settlement’s original cultivated land.

Flat Wood is the dark, diagonal block of conifers in the air photo. The junction of Headley Road and Hammer Lane is exactly at the bottom centre of the photo, from which the lane runs up and then along the left hand side of Flat Wood, its course marked by the bright green line of beech and birch trees. It used to be called Old Land Lane. Whitmore Bottom is at the top right corner of the photo, and the remaining green fields of Bulls Farm at centre bottom.

The area of Flat Wood (the dark conifer plantation) and the green fields of Bulls Farm. The junction of Headley Road and Hammer Lane is at bottom centre, from which the latter follows the line of the bright green beech trees diagonally up and then towards top left.

The medieval field banks still exist in and around Flat Wood, except for the south-east boundary where they were bulldozed away in the 1960s to make a forestry track. You can see the perimeter most clearly all along Hammer Lane, and especially in the north west at point P on the Lidar view below, where the bank is still several feet high. It would originally have had a hedge on top, and the ditch allowed to grow with brambles, the whole thing making a serious obstacle. Less clearly visible on the ground unless you know exactly where to look for them are the cross-banks between the fields, here marked by C, and the Lidar confirms that they are still generally surviving amidst the wood’s thick undergrowth. The cross-banks are about 180 yards apart, which would have originally been the length of an ox-drawn plough furrow. If you want to find them yourself then enter Flat Wood on the public footpath off of Bull Lane (BOAT 13) next to the house of Boscobel. Right here you can see a great example of the old perimeter bank, now much eroded but you can gauge the amount of soil that was originally dug out to make a ditch and bank at least six feet from base to crest. Then as you walk up the path into Flat Wood and count your paces. With careful eye you will find the cross-banks at the regular intervals. The name of the first field, now the site of Boscobel, has been lost, but after that you’ll walk through the medieval fields of Penyfield, Brodefield, Grenefield, Raylfield and finally Denefield. There is a reconstruction of 16th century Grayshott here.

The same view in Lidar.

There is lots of other interest in Flat Wood. The dimple above BC is a WW2 bomb crater. There are at least two charcoal hearths along the eastern edge, quite likely more waiting to be found, and probably saw pits too.

But back to the fields. Each was very roughly ten acres, which was one quarter of the standard medieval land measure of a virgate. It was a rule of thumb that an extended family needed a virgate of land in order to be largely self-sufficient. In Grayshott it seems that each family originally had one or two quarters, the rest being made up by them having access to the commons for rough grazing. If you look on the Lidar you can make out a shadow along the wood’s eastern edge. This is the break between the flat ridgetop and the steep valley side. The boundaries run across this contour. On the slope there are the remnants of ancient woodland, AW. On the Tithe Map below this is indicated by the different tree symbols. Our working theory is that each tenant had an area of flat land on which to grow crops, and an adjacent area of woodland which they could manage for coppice. The pattern is repeated in the old fields underneath Applegarth. This type of arrangement is very, very old and probably goes back to Grayshott’s Saxon farmers.

To the south of Flat Wood is Bulls Farm. We believe that this was the very first point of settlement, from which the fields radiated. The original farmstead was somewhere in the area of the old golf facility, marked BF. The house was deserted in the 16th century, another victim of the Black Death, and a new one eventually built on the other side of Hammer Lane in about 1771 (which is still there).

The Tithe Map shows some of Bulls’ original field pattern. On the Lidar you can easily see the surviving banks and points 1 and 2. There is no public access to these fields, but when conditions are right you can make out bank 1 from the iron bar gate on Hammer Lane (opposite the end of of Bull Lane). Look from the big lone oak tree across to the single story house (Whitaker’s old animal range) and you’ll see it. The line of bank 2 can be seen from the pavement along Headley Road, near the no 18 bus stop; it’s marked by a row of oak trees which are the remnants of the standards that were left for timber within the old cut-and-lay hedge. The short bank coming in from the west, between 1 and 2, is almost on the line of an original field boundary but is in fact a modern garden feature, a warning that artefacts on Lidar always have to be confirmed by visiting them.

And the Tithe Map.

That’s it for the moment. There is a huge amount of work to be done to explore and document Grayshott’s landscape. These Lidar pictures are a tremendous help; they confirm many things that we already knew of, point us towards some undiscovered ones, and pose quite a few new mysteries.

JC, February 2022.

… about Broomsquires?